Shared themes are not unusual in the world of mythology and folklore. Tolkien created characters like Eärendil and Túrin Turambar to explore themes like voyage, unavoidable tragedy, and familial taboo. Readers may find pieces of these characters reflected in previously-famous figures, like Odyssey from Ancient Greece and Kullervo from Finnish Kalevala. However, a parallel can be drawn from even less culturally familiar source: an epic creation myth of the Bugis from Sulawesi Island, Indonesia, titled La Galigo. Sawerigading, the central figure in the myth, is a rich and complicated character that has subtle parallel with Tolkien’s similarly iconic heroes.

About La Galigo

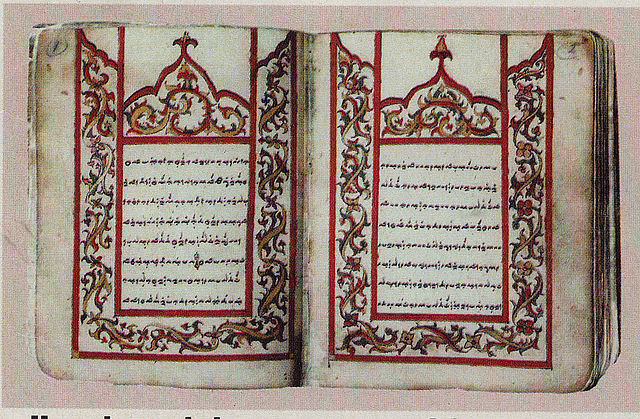

La Galigo is an epic poem depicting the creation myth of the Bugis ethnic group, although it also functions as everyday almanac and a part of sacred rituals. There had been several efforts to create the written versions, but the most famous one is probably Sureq La Galigo, created in the 19th century. There are no early versions of the manuscripts available due to climate, insect, and human destruction, but Sureq La Galigo is known as the most coherent one, containing around 300,000 lines and split into twelve parts. The most coherent fragments are kept at Leiden University Library, with the digitally scanned manuscripts available for free.

The author of the written piece, Queen Mother Colliq Pujie (1812-1876) from Tanete Kingdom in South Sulawesi, showed a long-term dedication akin to Christopher Tolkien with History of Middle-earth and Tolkien’s other posthumous works, in her efforts of transcribing La Galigo into the written form. Working nonstop for 20 years with the support of Dutch missionary and literature enthusiast B. F. Matthes, the queen aimed to preserve local literary heritage and inspire people through the wisdom and heroism contained in the poem (some fragments were transcribed during her exile in Makassar by Dutch colonial government).

La Galigo was written in pentameter, but each sentence was transcribed continuously without moving to the new paragraph, using a three-dot symbol called pallawa that functions as full stops, colons, and new alinea marking; the flowing model reflecting its origin as a work of oral literature (the symbol is used as an intonation marking when the poem is sung). The entire work contains numerous episodes with specific stories, and the characters serve as symbols for the life lessons and philosophy, transferred between generations.

Sawerigading, Eärendil, and “Union Between Two Worlds”

Among various characters mentioned in La Galigo, Sawerigading is perhaps one of the most interesting ones. Combining heroic qualities and human flaws, the appearance of Sawerigading basically kick-starts the story in “the middle world”, the poem’s equivalent of earth. He also reflects several themes you can find in the story of Eärendil, especially their connections to two different worlds as well as their “voyages in mission”.

The union between two worlds are reflected in their births. Eärendil was the son of Tuor and Idril, a Man and Elf that descended from the Three Houses of Edain and Finwë-Indis union, respectively. He was a result of the few successful unions between the two races, and his descendants later would play important roles in the history of Middle-earth. Sawerigading was the grandson of La Toge Langi Batara Guru (representing Boting Langiq, “the upper world”) and We Nyili’ Timo (representing Toddang Toja, “the underworld”). The union between these representatives of their respective worlds was an effort of the deities to populate the barren middle world.

At one point in the poem, Sawerigading conducted a voyage to China, going through several adventures, including surviving a devastating earthquake in one of his stops and getting involved in a sea battle that became a part of his courting efforts toward a Chinese princess called We Cudai. Afterward, Sawerigading and his wife were called to the underworld, while his sister Tenriabeng and her spouse were lifted to the upper world. Their children later married and became the first true rulers of Luwu, the oldest kingdom of South Sulawesi. Meanwhile, the voyage of Eärendil was done to beseech the pardon and help of the Valar in the battle against Morgoth. While their direct assistance resulted in the sinking of Beleriand, the Host of Valar later emerged victorious.

The tales of both Sawerigading and Eärendil also mention the presence of a trusted ship. Vingilótë, Eärendil’s ship, was built from the birch wood of Nimbrethil, with the help of Cirdan the Shipwright. The boat is described as having silver sails, gold oars, and swan-shaped prowl, giving it a distinctive shape, especially when the boat was later hallowed, lifted to the sky along with its owner, and becoming The Star of Eärendil, the source of hope. Meanwhile, Sawerigading started his voyage with a magical boat made of welengreng (the tree of the gods) wood. In one of his sailing trips, a giant storm crashed his boat, turning it into three floating debris, believed as the source of inspiration for locals who found them to create the pinisi boats, later becoming significant tools for Bugis sailors in their seafaring journeys.

Interestingly, the presence of Elwing as a white bird that accompanied her husband Eärendil in his sailing could echo La Dunrung Sereng, a magical bird or rooster owned by Sawerigading. The bird acted as an envoy that carries Sawerigading’s messages or finds information for him. It is similar to how Elwing went to Alqualondë and told the Falmari there about the tumultuous history of Beleriand, and later persuaded them to sail their ships for the Host of Valinor. La Dunrung Sereng’s presence also reflects the ancient custom of using birds as communication tools, and birds even became the basis for the creation of Old Makassar script; also called ukiri’ Jangang-Jangang or “the bird script”, due to its basic forms resemble birds.

There is also a meta-example of parallel between Sawerigading and Eärendil regarding of the creation of middle world/Middle-earth. The Voyage of Éarendel the Evening Star, Tolkien’s first effort in creating a coherent story within his budding legendarium concept through a poem about the titular sailor, was inspired by a Ninth Century Anglo-Saxon poem titled Crist, which contains the word middangeard (Middle Earth). Just like how the poem fueled imagination, mystery, and conception of Middle-earth legendarium, the exploits of Sawerigading are believed as the mythological root of Bugis people and culture. According to Bugis mythology, Luwu, the earthly kingdom of Sawerigading, is the “center/middle part of the universe”.

Sawerigading, Túrin, and Familial Taboo

Episodes depicting the birth and growth of Sawerigading also create a parallel with Túrin Turambar, Tolkien’s iconic tragic hero. However, we could say that Sawerigading earned a “happier” ending, considering that La Galigo also has the elements of moral teaching, reflecting the cultural foundation of Bugis people in the middle world. Just like how the marriage of characters from the upper world and underworld can be deciphered as “striking the world’s balance” in loving union, aspects of familial taboo are also discussed within the story, creating a source of legitimacy in social norms.

To see how La Galigo plays the incest problem, we have to get back to the marriage of Sawerigading’s grandparents, Batara Guru and We Nyili’ Timo. Both were actually first cousins, and their marriage was deemed necessary to populate the barren middle world. In Tolkien’s world, marriages between distant cousins are quite common; famous examples include Aragorn-Arwen, Elrond-Celebrian, and Nimloth-Dior. However, marriages, infatuations, or relationships between first cousins and blood siblings are the harbinger of disasters, unlike this particular wedding in La Galigo. We see how Maeglin conspired with Morgoth with the promise of possessing his cousin Idril, and brings the fall of Gondolin, or how Túrin Turambar married his sister Nienor, fulfilling the tragic prophecy and reflecting the fate of his inspiration source, the Hapless Kullervo.

In La Galigo, the birth of Sawerigading was marred with bad prophecy, not unlike the cursed prophecy that follows Túrin’s father, Hurin, and his descendants. His grandparents’ union resulted in a son named Batara Lattu, who later marries a woman named Sangiang. After seven years of being barren, they decided to ascend to the upper world and beseeched Puang Patotoe, the ruling god of the upper world, for children. Unfortunately, their desperate ascension happened during ulessada, or “the month of prohibition”. When Batara Lattu and Sangiang expressed their hopes for a boy and a girl, Puang Patotoe asked them to promise that they will separate the children, lest they will fall in love and get involved in a forbidden relationship.

The birth of Sawerigading was marred with difficulties, symbolizing discords and conflicts, mirroring Túrin’s series of misfortunes following the Battle of Unnumbered Tears, from his father’s capture and torture by Morgoth to his baby sister Lalaith’s death due to plague. On the contrary, Sawerigading’s sister, We Tenriabeng, brought forth peace and calmness with her birth. Their parents immediately separated them for fear of causing calamities if the siblings grew up together and fell in love, resulting in salimara (incestuous relationship). The siblings later had a chance encounter when they grew up, without knowing each other’s identity, and they fell in love. However, unlike how Tolkien wrote the story of Túrin, Sawerigading and Tenriabeng didn’t get tragic ending. Their parents managed to separate them once again, imploring Sawerigading to conduct the aforementioned voyage and find a wife in different land, resulting in marriage with Princess We Cudai, whose beauty was comparable to his sister.

Salimara is considered a serious transgression among Bugis people. In La Galigo, salimara is not only a dark blotch in one’s family reputation, but also the cause of calamities such as famine and large-scale natural disasters. By repeating these stories in oral and written forms, Bugis people make sure that the same transgression doesn’t happen in their communities, and this wisdom is taught from generation to generation. Incestuous love also happens to be the source of one of the biggest tragedies in Tolkien’s legendarium, perhaps one of his darkest tales.

The interesting parallel between major characters in Tolkien’s legendarium and Bugis epic creation myth cannot be separated from the major themes explored in both works. Through wisdom, knowledge, patient writing and transcribing works, and deep understanding about mythology, surprising connections can be made among their characters, especially related to the shared themes that all cultures in the world have at some points.

Sources:

Akhmad, Usman Idris. Siregar, Leo. Mitos Sawerigading dalam Epos La Galigo: Suatu Analisis Struktural. Etnosia: Jurnal Etnografi Indonesia (2018), 3 (2): 224-249.

Carpenter, Humphrey. 2000. The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien. Boston: HoughtonMiffin.

Cotterell, Arthur. Storm, Rachel. 2005. The Ultimate Encyclopedia of Mythology. London: Anness Publishing.

Tolkien. J. R. R. 1992. The Book of Lost Tales part 1. Christopher Tolkien (ed). New York: Del Rey.

Tolkien. J. R. R. 1992. The Book of Lost Tales part 2. Christopher Tolkien (ed). New York: Del Rey.

Tolkien, J.R.R. 1999. The Silmarillion. London: HarperCollins.

Tolkien, J. R. R. 2015. The Story of Kullervo. Christopher Tolkien (ed). London: HarperCollins.